High Speed and Light Alloy Trains

In the US, high speed trains are a vision of progress which came true between the two world wars. But mass produced cars and commercial flights fettered their development. Until now

by Alberto Pomari e Michele Sambonet

High speed trains have had no luck in the United States. The latest attempt to develop a modern infrastructure of fast public transport clashed in California against the pressure of contrary lobbies, delays in construction sites, costs which trebled with respect to forecasts. Launched in 2008 with a 30 billion dollar budget, the fate of the “Bullet train” meant to connect San Francisco to Los Angeles in 2 hours and forty minutes (with a future extension to Sacramento) is increasingly at risk. Not just because of the technical difficulties in the construction sites, which postponed the date when works should end from 2020 to 2033, but even because of the uncertainty of the financial funding of the works (entrusted to a public-private consortium) whose costs apparently skyrocketed to almost 100 billion dollars for 840 kilometres of the new railroad. Adding to this the bipartisan perplexity and in some cases the opposition of the current political world in California, the outlook of the project is gloomy. And yet high speed trains were conceived and took shape in the United States and in a very complex moment. With the Great Depression of the Thirties and the country going through a fully-fledged recession, American railways with their superb classical trains lost passengers. Trains looked like splendid luxury buildings on wheels, but they travelled too slowly. Carriages weighing 80-100 tons each formed 1,500-ton trains which were dragged at speeds of up to 150 km/h by gigantic steam locomotives which, in spite of these performances, could not compete against the increased presence of airlines or cars, which were covering miles and miles on increasingly developed roads. Railways had to adopt a speed policy with lighter and more streamlined vehicles. Managers of the American rail lines in the Thirties were convinced that the self-propelling semi-trailer train would have saved the railways.

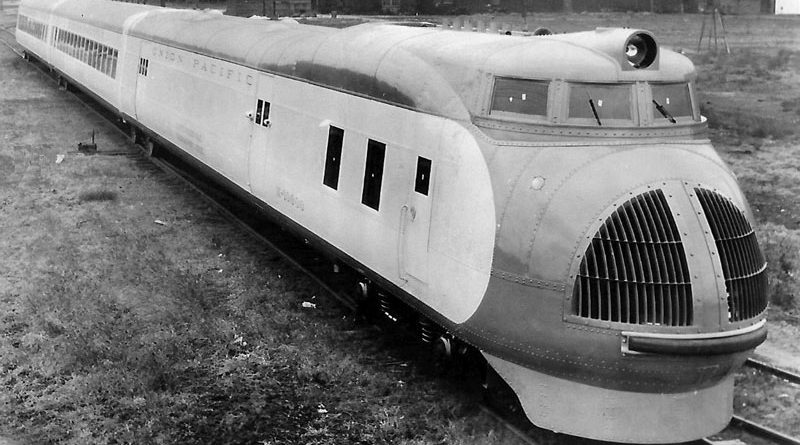

Union Pacific M-10000, an aeronautical design on tracks

In February, 1934, Union Pacific presented a train conceived along criteria which were typical of aeronautical design. Their construction was entrusted to the well-known Pullman-Standard company, which created a carriage with riveted aluminium sheets and a highly streamlined design. The train, mounted on ordinary two-element Jacobs trolleys, was made up of three units, a drive unit with a luggage compartment and two cars. The project was due to Martin P. Blomberg, an engineer from Pullman, who turned to the Electro-Motive Corporation to produce the mechanical part. The drive section had a driving Winton (GM) motor with commanded ignition which could deploy 600 hp. The two electric motors, produced by General Electric, had an effect on the first front trolley. Unfortunately we do not have information regarding the alloy used for this material and not even on the thickness of the metal sheets. We can only suppose that aeronautic-type, class 2000 or 7000 alloys were used for this project.

Coloured in yellow and brown, M-10000, nicknamed “Little Zip”, was the pioneer of automatic self-propelling semi-trailer trains built in aluminium and was also the first streamliner to begin its active service on the American network. During the same year the well-known keeled steam locomotives appeared, with their well-coordinated carriages and a unique design in perfect Art Déco style. Named City of Salina, Union Pacific’s M-1000 carried out a regular daily service on the Kansas City-Salina line, when it was prematurely broken down to provide the aluminium, with which it had been built, to the war industry.

The record of the Burlington Zephyr, 1934

In the United States it was necessary to move faster and for this reason the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q), which managed the important Chicago-Denver, at the beginning of the Thirties was convinced by a project by Edward G. Budd, founder and president of the Budd Company in Philadelphia, to relaunch the passenger service with a train having a completely new, cutting-edge profile. The project stemmed from a close cooperation with General Motors, which like Budd wanted to conquer the world of railways after the automotive industry. For the carriage body, Detroit’s engineers suggested stainless steel, welded using a new process patented by Budd. The design of the train’s streamlined profile, with a distinctive inclined front end, was created by Albert Gardner Dean, an engineer who had worked as an aeronautical designer. Named Zephyr and launched with an advertising campaign such as only Americans are capable of, this streamliner soon set its record: in May, 1934, it succeeded in covering the 1,633 kilometres between Denver and Chicago in 13 hours and five minutes, in a non-stop race at an average speed of 124 km/h, with peaks of 180 km/h. The Pioneer Zephyr is today on show at Chicago’s “Museum of Science and Industry”.

Union Pacific M-10001 and M-10002

Union Pacific’s reply to Zephyr’s record did not take long; in October, 1934, M-10001 was introduced, nicknamed “Canary Bolt”, similar to its predecessor but made up of six elements. It had a Winton (GM) 900 hp engine, this time diesel powered. It was immediately put to the test and travelled coast to coast from Los Angeles to New York, in just 57 hours, thereby setting a new record. After two months of intensive testing, M-10001 went back to the Pullman-Standard factory, for some changes and to replace the engine with a more powerful, 1200 hp one. Having started regular service, in 1935, named “City of Portland”, it cut down journey times for the over 3,400 km between Chicago and Portland (Oregon) from 58 to 40 hours.

Even this self-propelled semi-trailer train was demolished in 1941 to provide the aluminium with which it was built to the war industry. The engine and many electrical and mechanical components were recovered and used on another train.

In May, 1936, M-10002, renamed “City of Los Angeles”, began its service on the Chicago-Los Angeles route. M-10002 unlike its predecessors had a double BB+BB independent motor, with a 1200-hp diesel engine on the first unit and a 900-hp engine on the second unit. The convoy, articulated on Jacobs trolleys, was made up of nine carriages. Just like the previous trains with the same aspect, this train was built in aluminium by Pullman-Standard, the two diesel engines were Winton motors made by GM) and the eight electric motors and equipment were made by General Electric. Renamed “City of Portland” in 1937, it ended its career in 1943, when it met the same fate as the other two aluminium convoys.

The “competition” which began before the war between steel and aluminium continued after the war, but only at the end of the Seventies the properties of the two materials, especially aluminium, began to be exploited fully.

Acknowledgments

Heartfelt thanks go to Clive Lamming for the precious help provided in writing this article.